Case Report CFI 2/2023 – 10x Genomics vs. NanoString – Provisional Injunction I

UPC Case Law | 03.01.2024

1. Background and Summary

Three and a half months after opening its doors on June 1st, the UPC issued its first substantive decision in case UPC_CFI_2/2023, a request for a provisional injunction (“PI”) filed by the US company 10x Genomics and its licensor Harvard University against competitor NanoString. The request was filed on June 1, 2023, a two-day hearing took place on September 5 and 6, 2023, and on September 19, 2023, the Munich Local Division (“LD”) granted its first provisional injunction. The full reasoned decision (113 pages!) was published on the UPC website on September 28, 2023. With that, the Munich LD clearly intended to send a signal that the new court is ready and able to swiftly and fairly deal even with complex biotech cases such as this one.

Specifically, the LD found that NanoString’s CosMx Spatial Molecular Imager infringes EP 4 108 782 (“EP’782”), a European patent with unitary effect (EP-UE), and that all relevant factors weigh in favour of granting a provisional injunction (PI) with effect for the 17 UPC countries, including Germany, France, Italy, and the Netherlands. Interestingly, 10x Genomics had also filed a further PI requestagainst NanoString based on a closely related patent, EP 2 794 928 (“EP’928”), a classic EP. However, this request was rejected by the LD on October 10, 2023 for lack of infringement, doubts about validity, and lack of urgency (case no. UPC_CFI_17/2023).

The registered owner of both patents, EP’782 and EP’928, is the President and Fellows of Harvard College, who acted as co-plaintiff, with 10x Genomics alleging that it holds an exclusive license. The patents originate from the same priority application and pertain to the detection, identification and/or quantification of analytes in a sample. In particular, they relate to a multiplexed biological assay and readout, in which a multitude of detection reagents comprising one or more probes are applied to a (preferably biological) sample, allowing the detection reagents to bind target molecules or analytes in the sample, which can then be identified in a temporally sequential manner. In a preferred embodiment, the analysis is conducted in situ on a biological sample mounted to a support. The patented device and methods thus enable the simultaneous analysis of a multitude of analytes (e.g., RNA or proteins) in a biological sample (e.g., a tissue sample), which can be of interest e.g., for monitoring gene or protein expression in different types and regions of tissue.

The panel of the LD consisted of two legally qualified German judges, Dr. Matthias Zigann (presiding judge), and Tobias Pichlmaier (judge-rapporteur), a Dutch legally qualified judge with an MS degree in molecular biotechnology, András Kupecz, and Eric Enderlin, a French technically qualified judge in the field of biotechnology.

2. The Oral Hearing

The LD’s first hearing, which was held in German, already provided interesting insights into the approach of at least this local division to such proceedings. It was particularly remarkable how similar this hearing was to a classic hearing in a German provisional injunction case. The hearing started with an extensive introduction into the case by the presiding judge Dr. Zigann, from which the parties could already take strong hints on the critical issues that they should primarily address in their subsequent pleadings, and the court’s preliminary views on these issues. He also cautioned the parties not to spend too much time on issues that the court had considered but did not think merited further discussion. Throughout the subsequent pleadings by the parties, the judges, in particular all legally qualified judges, proved to be very active. Time and again, they poked the party representatives with questions, and sometimes quite tricky ones. The panel was clearly well-prepared and expected the same from the parties.

Initially, Dr. Zigann hinted that the court wanted to conclude the discussion on day 1, and the hearing was broadly structured into the issues of (a) infringement, (b) validity and (c) other legal arguments. However, it turned out at the end of day 1 that both the parties and the members of the court were fairly exhausted after spending the whole day in an overheated and quite small hearing room with no air conditioning. Opening the windows helped to allow at least some oxygen in but was impeded by the incredible noise of a nearby construction site. As the defendant still wanted to present further parts of its invalidity case and arguments why – with regard to the balance of interest a preliminary injunction should not be granted - and estimated that this would take another two hours of speaking time, the court used the following day to conclude the discussion and to allow both parties the full right to be heard. The hearing was then finished at about noon on day 2.

Even though the Presiding Judge presented the court’s preliminary view in the beginning of the hearing, the panel made a sincere effort to appear fair, unbiased and open to be persuaded by (better) arguments from the parties. No impartiality objections were raised by any of the parties.

A recurring theme, both in the written proceedings and during the hearing, was that the UPC’s Case Management System (CMS) is still riddled with errors. A particular manifestation of such an error was a message that the UPC CMS sent to the parties‘ representatives informing them that the hearing would only start at 10 am, not 9 am as provided in the summons. It turned out that this message was generated automatically without input by or information to the panel. As a result, one of the parties appeared 30 min late, but with a good excuse in view of the circumstances. Mr. Zigann admonished the parties (and the public) that the only relevant time is the one shown on the summons signed by the Presiding Judge. Hence, for the time being, just relying on the CMS is no good idea. We can only hope that the CMS‘ teething problems will be overcome some day, but according to Mr. Zigann there are quite a lot of them, and the CMS is certainly not yet where it should be.

The court dealt with these and other peripheral issues very pragmatically and tried to spend as little time on them as possible. Moreover, the judges were clearly more interested in an in-depth discussion of the substantive issues, i.e., infringement and in particular validity, rather than spending much time on questions of urgency, irreparable harm, the licensing relationship between 10x Genomics and Harvard, anti-trust law, or territorial scope of the decision (all issues where the defendant had filed objections).

A particularly interesting aspect of this preliminary injunction case was that plaintiff did not assert the patent as granted, but according to a slightly limited claim 1 (main request). During the hearing plaintiff even filed an auxiliary request including a further amendment to claim 1, which the German Federal Patent Court had preliminarily found sufficient to establish novelty and inventive step of the parent of the patent in suit. While the court reserved its decision on admissibility of this auxiliary request (and eventually did not come to it, as the main request was successful), it became at least transparent that it is not an absolute no-go to try obtaining a preliminary injunction based on a limited version of the patent.

3. The Decision

It is anything but easy to condense a 113 page decision to its essence on 2-3 pages, so readers taking a deeper interest should definitely consult the original decision, of which German and English versions are provided on the UPC’s website here.

A. Admissibility

The LD Munich considered that it was competent to hear the dispute according to Art. 33(1)a UPCA, since defendant provided “shipping now” information for their products on their website in the EU and had further advertised it in Germany by presentations. The court viewed this as the conclusive demonstration of a (potentially) infringing offer also in Germany. According to the LD, this is sufficient to assume competence of the LD Munich, even if the legal analysis were to result in a finding of non-infringement or invalidity.

The LD further rejected Defendant’s multiple objections that Plaintiff’s application for provisional measures did not satisfy the formal requirements of Rule 206(2) in conjunction with Rule 211. It seems that the LD does not take a very strict stand regarding these formal requirements. For example, Defendant complained that the application contained only very sketchy allegations regarding validity, in addition to a reference to the preliminary opinion of the German Federal Patent Court in the parent patent, whereas Rule 211 would require “reasonable evidence to satisfy the Court with a sufficient degree of certainty (…) that the patent in question is valid". However, the LD Munich held that in view of the principles on the burden of presentation and proof that apply to the submission on validity – at least in inter partes proceedings, as in the present case – according to Article 54 UPCA, the requirements for the submission on the validity of the patent at issue set out in Rule 206(2)(d) RoP must not be overstretched.

Defendant further asserted that the application is inadmissible for lack of a legal interest in view of claimant’s enforcement of a preliminary injunction in Germany that was previously issued by the District Court of Munich. However, the LD Munich rejected this objection: While enforcement of a judgement of the court of a contracting state of the UPCA only concerns infringements of the judgement in that contracting state, decisions of the UPC in the case of a European patent have uniform effect in all contracting states of the UPCA. Thus, in view of the territorial scope of decisions of the UPC in relation to decisions of the courts in the contracting states, there is generally a need for recourse to the UPC. In addition, the court noted that Claimants asserted the parent patent before the Regional Court Munich I, so that the subject matter of the dispute is different.

The LD further held that both claimants had standing to sue. Claimant Harvard had this right as the proprietor of the patent, Art. 47(1) UPCA, whereas 10x Genomics had this right at least as a non-exclusive licensee, Art. 47(3) UPCA. Defendant’s numerous objections that this license was invalid for violation of the Bayh-Dole-Act under US law were rejected. The LD argued that claimants had at least demonstrated that the patent proprietor had been given prior notice of the action and that the licence agreement permits bringing an action before court. This is sufficient to satisfy the requirements of Art. 47(3) UPCA.

B. Validity

B.1 Standard of Evaluation

The LD was also convinced with the "sufficient certainty" required under Article 62(4) UPCA and Rule 211(2) RoP, namely with even clearly preponderant likelihood, that the patent is valid. From the Local Division's point of view, even a simple "preponderant likelihood" would have fulfilled the “sufficient certainty” requirement.

While the validity of the patent is not expressly mentioned in Article 62(4) UPCA as a point regarding which it has to be convinced with a sufficient degree of certainty, in contrast to Rule 211(2) RoP, the LD held that only a person who relies on a patent that is valid to the satisfaction of the court can be deemed to be the rights holder within the meaning of Article 62(4) UPCA.

B.2 The Patent in Suit

The LD first provided a thorough explanation of the subject-matter of the patent in suit and a structured feature analysis of claim 1 in colour, which is reproduced here:

A method for detecting a plurality of analytes in a cell or tissue sample, comprising

1. (a) mounting the cell or tissue sample on a solid support;

2.1 (b) contacting the cell or tissue sample with a composition comprising a plurality of detection reagents,

2.1.1 the plurality of detection reagents comprising a plurality of subpopulations of detection reagents;

2.2 (c) incubating the cell or tissue sample together with the plurality of detection reagents for a sufficient amount of time to allow binding of the plurality of detection reagents to the analytes; wherein

2.2.1 each subpopulation of the plurality of detection reagents targets a different analyte, wherein

2.2.2 each of the plurality of detection reagents comprises: a probe reagent targeting an analyte of the plurality of analytes, and

2.2.3 one or a plurality of pre-determined subsequences, wherein the probe reagent and the one or the plurality of pre-determined subsequences are conjugated together;

3.1 (d) detecting in a temporally-sequential manner the one or the plurality of pre-determined subsequences, wherein the detecting comprises:

3.1.1 (i) hybridizing a set of decoder probes with a subsequence of the detection reagents,

3.1.1.1 wherein the set of decoder probes comprises a plurality of subpopulations of decoder probes, and wherein

3.1.1.2. each subpopulation of the decoder probes comprises a detectable label,

3.1.1.3. each detectable label producing a signal signature;

3.1.2 (ii) detecting the signal signature produced by the hybridization of the set of decoder probes ;

3.1.3 (iii) removing the signal signature; and

3.1.4 (iv) repeating (i) and (iii) using a different set of decoder probes to detect other subsequences of the detection reagents, thereby producing a temporal order of the signal signatures unique for each subpopulation of the plurality of detection reagents; and

4. (e) using the temporal order of the signal signatures corresponding to the one or the plurality of the pre-determined subsequences of the detection reagent to identify a subpopulation of the detection reagents, thereby detecting the plurality of analytes in the cell or tissue sample.

B.3 Claim Construction

Next, the LD construed several claim features that were in dispute between the parties. For instance, the LD held that the term “cell or tissue sample” means a sample that is still recognizable as a cell or tissue. Defendant’s objections that the patent would also cover pre-treated or processed samples of any kind was rejected. According to the LD, the claim also requires the mounting of the cell or tissue sample on a solid support. This means that in any case the sample must not be pre-treated to such an extent that it is in fact no longer a cell or tissue sample. Consequently, DNA that has been isolated from a cell and amplified, as it was described in one prior art reference, was not considered as anticipating this claim feature.

Conversely, the LD construed the term “subpopulation of detection reagents” broadly by not requiring that all members of this subpopulation must be identical, but merely that they all bind to the same target (analyte). This helped patentee later in the infringement discussion, see below.

Furthermore, the LD considered what had to be repeated according to feature 3.1.4 and came to the conclusion that evidently not only steps (i) and (iii) would have to be repeated to arrive at a meaningful measurement result, but also step (ii), i.e., the detection of the signal signature produced in each run. The court strongly rejected a purely literal construction of the claim, as suggested by the Defendants, as “technically obviously absurd. A person skilled in the art will always seek to make the content of a patent make sense.” This is reminiscent of the generous German tradition in interpreting claims (FCJ Rotorelemente, X ZR 18/17), but also of the EPO’s principles as set forth in T 190/99, i.e., that the skilled person when considering a claim should rule out interpretations which are illogical, or which do not make technical sense.

Finally, the LD clarified the meaning of feature 4, using the temporal order of the signal signatures to identify the detection reagents and thus to detect the analytes, to mean that the temporal order of the signal signatures is the (only) means according to the patent for identifying the subpopulation of detection reagents. No other means are mentioned.

B.4 Legal Standard in Summary Proceedings

With that, the Court turned to the legal standard according to which validity must be shown in summary proceedings. It is worthwhile reproducing the LD’s conclusions here literally:

Neither the UPCA nor the Rules of Procedure specify in any greater detail which degree of conviction for validity is required in that regard. In principle, any degree of likelihood can be considered ("some likelihood", "preponderant likelihood", "substantial likelihood" (Article 55(2) UPCA), "high likelihood", "likelihood bordering on certainty", to name just a few examples of degrees of likelihood). The correct understanding of the term "sufficient certainty" must be based on the specific purpose of the conviction. In the case of Article 62(4) UPCA and Rule 211(2) RoP, it must be taken into account in particular that it is a matter of ordering temporary provisional measures in summary proceedings (Rule 205 RoP) under Rule 213 RoP, not final orders within the meaning of Article 63 UPCA. In view of the provisional nature of the measures and the limited possibilities of discovery in summary proceedings in relation to proceedings on the merits, it follows that the standard of likelihood must be lowered. Therefore, a likelihood bordering on certainty cannot be demanded. Ultimately, for a sufficiently certain conviction of the validity of the patent at issue, a preponderant likelihood is necessary, but also sufficient. Therefore, for a sufficiently certain conviction on the part of the Court, it must be more probable that the patent is valid than not valid.

The LD Munich then explicitly rejected defendant’s attempts to rely on the German case law which set out that the revocation of the patent must merely appear possible based on the prior art on file. This case law was seen as irrelevant for the interpretation of the UPCA and the Rules of Procedure. The LD also did not follow defendant’s argument that there cannot be a presumption of validity of a European patent that has not yet undergone opposition proceedings in view of the high revocation rates before the EPO. I held that, pursuant to Rule 211(2) RoP, the Court has to make a decision on a case-by-case basis with regard to the concretely asserted patent in view of the validity. It follows from the necessity of a case-by-case assessment that general statistical findings on the frequency of revocation are not to be taken into account.

B.5 Burden of Proof

Next, the LD imposed the burden of proof regarding validity on the defendant, arguing as follows:

According to the principle laid down in Article 54(1) UPCA, the burden of proof for facts relating to the lack of validity of the patent at issue lies with the Defendant, because the Defendant claims that the patent at issue will have to be declared invalid. This also corresponds to the distribution of the burden of proof in revocation proceedings and in the case of counterclaims for revocation. Insofar as Article 62(4) UPCA or Rule 211(2) RoP provides that the court may order the Claimant to submit evidence on the validity of the patent, this does not mean a departure from this principle in the sense of a different burden of proof rule for the injunction proceedings. Article 62(4) UPCA and Rule 211(2) RoP are "may" provisions, so that the court has a discretion.

B.6 The Person Skilled in the Art

Following these introductory remarks, the LD turned to the specifics of the validity case, beginning with a definition of the person skilled in the art, who was defined as a chemist or biologist with a university degree in the field of biochemistry who has experience in the field of detection strategies for biomolecules. The LD took this opportunity for some self-promotion, by stating that “the Local Division is staffed with a relevant technically qualified judge. One of the legally qualified judges also has a university degree (MSc) in molecular biology.”

B.7 Added Matter

This was followed by a brief discussion of added matter, which defendant lost due to the Court’s construction of features 3.1.4 and 4, which brought these features into accordance with the content of the application as filed.

B.8 Novelty

On novelty, the court first adopted the EPO gold standard, I.e., that in order to be able to identify a lack of novelty, the subject matter of the invention must clearly, unambiguously and directly result from the prior art. This applies to all claim features. Claim 1 of the patent was then found novel over D6 (Göransson) because this reference did not disclose a cell or tissue sample according to the LD’s understanding of the claim, but “amplified single molecules” instead. Moreover, the court saw a difference in the claim requiring continued binding between the analyte and the detection reagent, whereas Göransson employed various cycles of hybridization/dehybridization. D12 (US 2010/0151472) was also not viewed as novelty-destroying because it does not show, according to the LD, that a temporal sequence of signal signatures concerning the same detection reagents is generated in a temporally sequential manner by repeated hybridisation in order to identify them.

B.9 Inventive Step

The LD’s decision on inventive step started with a – perhaps surprisingly – clear commitment to the EPO’s problem-solution-approach. In particular, the concept of a “closest prior art” as a starting point was adopted without much discussion. The court stated the following:

The (closest) prior art to be used for determining lack of inventive step is usually a prior art document disclosing an object developed for the same purpose or with the same aim as the claimed invention and having the most important technical features in common with it, i.e. requiring the fewest structural changes. An important criterion in choosing the most promising starting point is the similarity of the technical task. In this respect, more weight should generally be given to aspects such as the designation of the subject matter of the invention, the formulation of the original task and the intended use as well as the effects to be achieved than to a maximum

number of identical technical features.

This statement might well have been taken 1:1 from the Case Law Book of the Boards of Appeal. It remains to be seen whether this will be the official policy of the UPC for the years to come, and in particular whether the Court of Appeal will follow this reasoning.

Turning to the prior art in this case in more detail, the LD Munich rejected the primary reference invoked by the defendants (D8, Duose 2010) as “far removed” from the subject-matter of claim 1. In the court’s view, the principle of D8 could be described as using the same substrate in a first run for the detection of a marker (analyte) A, while in a second run it is to be used for the detection of a marker (analyte) B. This idea of using a colour- providing substrate several times for the detection of different analytes was seen as substantially different from the principle according to claim 1, namely of detecting an analyte to which a detection reagent has bound by producing a temporal order of signal signatures on that detection reagent. In the court’s view, this does not render the invention obvious.

The LD also saw no concrete technical reason for combining D8 with Göransson (D6); in particular, it was not apparent to the Court why the person skilled in the art should have been motivated to deviate from the solution taught in Duose (D8) for an in situ analysis for cell or tissue samples and instead use a fundamentally different method from a fundamentally different context in order to be able to detect more analytes, as taught in Göransson (D6). The court even opined that D8 teaches away from the claimed invention.

The LD further rejected the defendant’s attempt to derive obviousness starting from Göransson (D6). It opined that the skilled person would not have used Göransson as a realistic starting point, let alone as the closest prior art, in view of the problem (Aufgabe) according to the patent. Göransson was not aimed at detecting a large number of analytes in a cell or tissue sample. Rather, Göransson contemplated the use of amplified single molecules (ASMs) in "a new random array format". While Göransson does disclose a similar "encoding and decoding method" to that used in the patent at issue, it does so in a very different context, namely ASMs on an array. This method would not, without hindsight, "transport" the skilled person from an array of ASMs to a cell or tissue sample (mounted on a solid support) without specific motivation. The Local Division, however, was unable to recognise such a motivation. In addition, the LD spotted a further relevant difference between the method used in Göransson and the method used according to claim 1.

An expert opinion presented by the defendants was likewise dismissed by the LD Munich as being based on a retrospective view (ex post facto analysis) with knowledge of the invention; even if one wanted to follow the opinion’s hypothesis that there were no insurmountable obstacles to combine the teachings of D8 with D6, it would not necessarily follow that the person skilled in the art would actually have done so. It would, however, have been necessary to show this latter point to establish a lack of inventive step. It may thus be concluded that the LD Munich, in evaluating inventive step, applied a mix of concepts taken from German case law (motivation required) and EPO case law (could-would test), which in the court’s view led to the same result in this case. A further expert opinion by the Swedish patent office presented by the defendant, which concluded that the claimed invention was obvious over a combination of D8 with D6 and further references, did not even make it into the LD’s decision. The same, however, also applied regarding the preliminary opinion by the German Federal Patent Court on the validity of the parent patent, which had come to a “mixed result” (patent as granted invalid; patent according to auxiliary request 1 valid).

An even further reference, US 2010/0151472 (D12), was unsuccessfully used by the defendants. The LD thought that the person skilled in the art would not have chosen D12 as the starting point for their considerations in view of the objective underlying the patent at issue and concluded therefrom that the combinations put forward for discussion by the Defendants in this context are not relevant either.

B.10 Sufficiency of Disclosure

Regarding sufficiency of disclosure, the LD Munich again applied the EPO standard, stating that:

A successful defence of insufficient disclosure requires raising serious doubt, substantiated by verifiable facts, that a skilled reader of the patent would not be able to carry out the invention on the basis of his general knowledge of the subject matter.

Again, the defendant had mounted several objections regarding (allegedly) insufficient disclosure, yet the LD Munich soundly rejected all of them. One of them failed because it was based on a claim construction that the court had rejected; another one failed because the LD Munich did not consider it fatal to the invention that it had not been shown how certain embodiments at the fringes of the claim can be carried out:

To the extent that the Defendants further argue that the invention cannot be carried out with extremely short decoder probes and that the patent does not provide the person skilled in the art with instructions on how a decoder probe with only a single nucleotide can nevertheless be used for detection, the Court does not find this to be insufficient disclosure.

The person skilled in the art knows from his general knowledge of the art and also from the patent description (paragraph [0059]) that there are decoder probes of different lengths; also on the basis of the claim and the description of the patent at issue the Defendants have not shown any reason to doubt that a person skilled in the art is able to choose an appropriate sequence length for the implementation of the patented method.

C. Infringement

C.1 Standard

The Local Division was convinced with sufficient certainty, namely with at least a high degree of probability, that the Defendants infringe the patent at issue both directly and indirectly.

C.2 Detailed Analysis

The court noted that infringement of many features was not disputed and focused on those on which the arguments of the parties were centered.

Regarding feature 2.2.1, the defendant’s submission had to fail in view of the court’s construction of this feature. According to the defendants, it is decisive for an allocation to a subpopulation that the reagents are identical at the molecular level, which must also apply to the probe reagent. However, on the Claimants' understanding, which the Court adopted, a subpopulation meeting the requirements of this feature is not necessarily characterised by an identity in the probe reagent, but only by the fact that each detection reagent belonging to the same subpopulation binds to the same target analyte. This was the case in defendant’s device.

The most interesting non-infringement argument revolved around features 3.1.4, i.e. “repeating (i) and (iii) using a different set of decoder probes to detect other subsequences of the detection reagents, thereby producing a temporal order of the signal signatures unique for each subpopulation of the plurality of detection reagents”, and 4. "using the temporal order of the signal signatures corresponding to the one or the plurality of the pre-determined subsequences of the detection reagent to identify a subpopulation of the detection reagents, thereby detecting the plurality of analytes in the cell or tissue sample”.

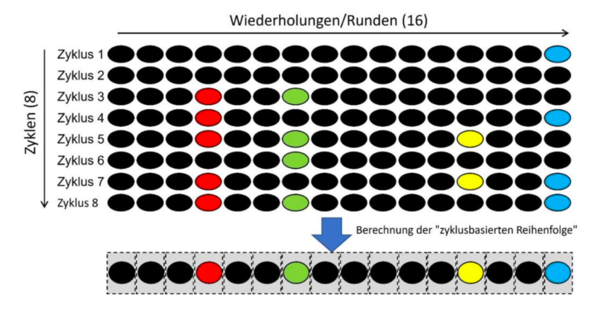

The defendants submitted that in their method a hybridisation cycle (which included 16 hybridisation rounds in each cycle) is repeated identically several times (in the example eight times, i.e. eight cycles). This was the only way to achieve a reliable and correct result. The temporal sequence of any signal signatures in the individual cycles (i.e. after rounds 1 to 16) is neither determined ("thereby generated") nor used to identify analytes. Such a temporal order (only rounds 1 to 16 of a cycle) would also not be unique for each subpopulation of the multitude of detection reagents. The temporal order of the signal signatures of the individual test rounds would not provide a sufficiently precise identity of an analyte. Therefore, in the Defendants' method, a cycle-based sequence is calculated instead of the mere temporal sequence and only this cycle-based sequence is used to identify analytes in order to obtain a reliable and correct result. The "temporal order" of the individual 16 test rounds per se, on the other hand, is neither unique for an analyte nor is it directly used for the identification of the analyte, as can be seen in the following schematic drawing:

The Local Division Munich was nonetheless not convinced and concluded that the defendants still apply the method of claim 1, albeit several times, and that it is not required by the claim that the result of each hybridization cycle is “correct”; it is sufficient that it is “unique” and that the end result of the method is a temporal order that allows the correct identification of a certain analyte.

For a similar reason, the court was also unwilling to follow the defendant’s argument that the final calculation of its “cycle-based order” was done on a server outside the jurisdiction of the UPC and there was no infringement of feature 4 in the UPC territory for that reason as well. The court thought that it is sufficient for infringement that the actual temporal orders of signal signatures are recorded inside the UPC territory. Defendant’s additional calculation step may not have been provided in the claim but is also not excluded thereby.

Regarding feature 4, the LD Munich provided the following opinion:

Claim feature 4 provides that the temporal order of signal signatures is used to identify a subpopulation of detection reagents and thus to detect the analytes. This claim feature can thus be understood as a mere indication of the purpose actually served by the order of signal signatures produced by the method in accordance with the claim (claim features 1 to 3.1.4), without expressing an independent method step in substance.

(…)

This makes it clear that feature 4 has no independent technical content, since the essential elements of the feature are already contained at least implicitly in the other features, so that the realisation of that feature already follows directly from the realisation of the other features. It is not apparent that this linguistically different formulation results in an additional technical meaning, in particular a further method step, which has not already been expressed in the other features. From the point of view of a skilled reader, feature 4 therefore merely describes the result of the method, i.e. the effect aimed at by the application of the process.

Thus, the court deprived the term “using the temporal order... to identify a subpopulation of detection reagents” of its literal meaning, by giving it a wide and purposive construction.

Therefore, the court concluded that defendant’s CosMx Spatial Molecular Imager (embodiment 1 according to the application for provisional measures) directly infringed claim 1 of the patent in suit as asserted by the claimant, to the extent that it is used for RNA analysis.

Embodiment 2 were RNA detection reagents used in the Molecular Imager. They were held to indirectly infringe claim 1, because the defendants offered and supplied them in the territory of the UPC for use in the method in accordance with the claim. In the LD Munich’s view, it was obvious to the Defendants that the contested embodiment 2 is suitable and intended to be used by their customers for a method in accordance with patent claim 1 in Germany and other UPC Contracting States, because the contested embodiment 2 is a means with which a direct act of use - the application of the method in accordance with claim 1 - can be realised, i.e., a means which is objectively suitable for direct patent use.

Embodiment 3 pertained to secondary probes designed to bind to the primary detection reagents that are bound to the analyte. They were also found to indirectly infringe claim 1 of the patent. However, as the analyte for which these secondary probes were offered by the defendants could have been either RNA (covered by claim 1) or a protein (not covered by the claim), the court found that an unconditional injunction regarding embodiment 3 would not have been appropriate:

However, since the contested embodiments 1 and 3 can be used not only for the detection of RNA, but also for the detection of proteins, an unlimited ban was not to be ordered with regard to these embodiments. In this respect, the Claimants only applied for a limited prohibition by affixing a warning.

Claimants further requested that defendants should not only cease and desist from using or offering the method according to the patent but also to discontinue it (“abzustellen”). This obviously raised the court’s eyebrows, because it was not quite clear what exactly claimants meant by “abstellen”. (Perhaps it was just a translation issue – the classic English translation of the German term “unterlassen” is “to cease and desist”, which could literally also be translated as “zu unterlassen und abzustellen”). In any case, the court held that there is no legal basis for any request going beyond a cease and desist order under the UPCA. Therefore, insofar as claimant’s wording was intended to make a remedy to eliminate the impact of the infringement, that means obliging the Defendants to recall the contested embodiments, this request had to be rejected. The Local Division therefore dismissed the application for an injunction to this extent.

D. Explanation of Court’s Orders

The LD Munich commented on the form of the order, defending the German tradition to formulate the cease-and-desist order by using the language of the claim, rather than a description of the defendants’ concrete embodiments. The court’s argument was this:

According to Art. 62(1) UPCA, the court may grant injunctions to provisionally prohibit the continuation of an infringement. A comparison with the measure under Art. 62(3) UPCA, which relates to potentially infringing products and is thus much more specific, shows that the Agreement grants the court a wide scope in the wording of the order to prohibit the continuation of infringements when ordering measures under Art. 62(1) UPCA. A limitation of the order to the specific designation or description of the contested products cannot be inferred from Art. 62(1) UPCA. It is therefore permissible to formulate the act to be prohibited under Art. 62(1) UPCA with the aid of the patent claim. In particular, this is also in accordance with Article 25 UPCA, according to which the subject matter of the patent determines the use to be prohibited; this is found in the respective patent claims concerned.

The LD Munich also had no objection to claimant asserting claim 1 only in a limited form. Indeed, claimant had deleted the variant that probe reagent targets an analyte of the plurality of the analytes and one or a plurality of pre-determined subsequences, thus requiring the use of a plurality of subsequences per probe reagent. Defendant objected to this deletion, arguing that claimants would assert a version of the claim that had not been granted and hence is non-existent. The LD Munich, however, disagreed with this objection, arguing that:

If a patent claim, as in this case, provides for several alternatives for the design of a product or method in accordance with the claim, it is permissible to select in the request for an order the one that is the subject matter of the contested embodiment or the contested process. A correspondingly limited formulation of the request for an order merely specifies the infringement to be prohibited, but does not mean that the patent at issue is asserted in a limited or ungranted version. A correspondingly restricted request for an order must be possible, because the Claimant could also describe the specific form of infringement in the request instead of reproducing the patent claim; in this case, it would be obligatory to refrain from describing an alternative claim that does not have the form of infringement.

While the latter is certainly hard to disagree with and corresponds to German practice, the assertion of a patent claim in a limited form may also have implications for the claim’s validity. The LD Munich did, however, not discuss this further in its decision. It even went one step further when discussing the auxiliary requests filed by the claimants during the oral proceedings, following a suggestion by the Local Division, which was made to dispel any remaining doubts on validity of the patent in suit. Unfortunately, the English translation of the decision is quite incorrect in this specific paragraph. The following is what we think is a more appropriate translation of the German original (paragraph no. 2 on page 83/84 of the German decision):

To the extent that the Claimants filed further auxiliary requests during the oral proceedings that were not further substantiated in writing, thus following a suggestion of the Local Division in order to dispel any doubts of the Local Division that might still exist after the question of the validity of the patent at issue had been discussed during the oral proceedings, the Local Division does not consider this to be a violation of the Rules of Procedure or of superior law. The indication given by the Local Division is in accordance with Article 42 UPCA and Rule 210 (2) ROP; addressing an indication by the court that concerns the wording of the request, by filing a corresponding auxiliary request cannot be considered a violation of the Rules of Procedure. Ultimately, however, this is not relevant, as no decision had to be taken on the auxiliary request.

This seems to indicate that the court might even have accepted an auxiliary request (that is, a further limited version of claim 1) filed only during the oral proceedings, at least if the court provided a hint to the parties (mainly the claimants) that such a request might be appropriate. In our experience, such hints were certainly not the practice of most national courts before the advent of the UPC, and it remains to be seen how the Court of Appeal will position itself in this respect.

E. Necessity of preliminary measures

The LD Munich concluded from Rule 206(2)(c) that provisional measures must actually be necessary; it is not sufficient that there is an (imminent) infringement. The following standards are to be kept in mind for the necessity of such measures:

According to the RoP, both temporal and factual circumstances are relevant for the necessity of ordering provisional measures. The relevance of temporal circumstances results not only from Rule 209(2)(b) RoP ("urgency") but also from Rule 211(4) RoP, according to which the court shall take into account an unreasonable delay in applying for provisional measures. The relevance of factual circumstances for the necessity of granting provisional measures results, for instance, from Rule 211(3) RoP, according to which, when deciding on the request for an order, the potential harm that the Claimant may suffer must also be taken into account in particular (while the potential harm for the defendant must be taken into account when weighing the interests).

The parties were in dispute whether claimants had filed their application in time and whether provisional measures were actually necessary. Defendants argued that claimants knew about the allegedly infringing acts for several months and even obtained and enforced a preliminary injunction in Germany against these acts. The filing of a further application for provisional measures at the UPC appeared unnecessary and vexatious to them and was alleged to be negligent conduct. The LD Munich, however, disagreed with this opinion and pointed out that the filing of the application for provisional measures occurred at the earliest possible date before the UPC, i.e., on 1 June 2023, and that the existence of a national provisional injunction does not remove claimants’ legal interest in the enforcement of a European patent with unitary effect:

There would have been no need to establish the UPC and a European patent with unitary effect (unitary patent) if adequate enforcement had already been possible on the basis of European (bundle) patents (without unitary effect). However, it is clear from the recitals of the UPCA that the enforcement of European patents without unitary effect is difficult due to the fragmented patent market and the considerable differences between the national court systems and is associated with considerable disadvantages. With the establishment of the UPC and the creation of the unitary patent, this state of affairs, which is correctly described as disadvantageous, should be improved and legal certainty thereby strengthened. The enforcement of a European patent without unitary effect, which must be carried out separately in all member states, is therefore not an equivalent means of enforcing rights in the case of infringement compared to the enforcement of a unitary patent before the UPC. According to the wording and the system, Rule 211(4) RoP accordingly refers only to the application for provisional measures under the UPCA and before the UPC. There are no indications that requests for provisional measures in the individual contracting states on the basis of a bundle patent or national patents could also be taken into account.

The LD Munich also considered a provisional injunction necessary in factual terms. According to the court, the necessity arises from the potential harm to the Claimants by the Defendants' infringing offers of the product. While the court acknowledged that irreparable harm threatened both the claimants if a provisional injunction was not granted and the defendants if a provisional injunction was granted, it concluded that the interest of the right holder in not having its rights infringed outweighs the interest of the potential infringer in securing market shares now through the continuation of the infringement, which it can no longer obtain later through a possible licence agreement.

The LD Munich further held that the order for provisional measures is also not precluded by the licence claim asserted by the Defendants against Claimant 2) (Harvard), because the existence of such a licence claim has not been established to the satisfaction of the Local Division. Defendant’s assertion of a licence claim was based on a contract between the NIH and Harvard University under US law. However, the LD Munich had doubts that the defendants were allowed to rely on any (hypothetical) obligation of Harvard to grant simple licenses as third-party beneficiaries. The court referred to and followed a decision by the District Court of Delaware where it was held that “NanoString has not plausibly alleged that it is a third-party beneficiary of the NIH grant agreement”. The defendants unsuccessfully tried to argue against this (appealable) US decision, relying on two party expert opinions by a US Professor, yet the Court expressed considerable doubts about these opinions in three respects: Firstly, it was not even certain to the court that legal opinions submitted to prove a legal assertion (in this instance existence of a licence claim under US law) constitute expert evidence at all within the meaning of Rule 181 RoP (according to Article 54 UPCA, the subject matter of the evidence is facts). Secondly, the court expressed doubts whether the party expert opinion is “an independent and objective expert opinion pursuant to Rule 181 (2) RoP”; the “somewhat disconcerting and uninitiated engagement of the expert" with the internet presence of the Claimant's representatives and the overall tendency of one-sided legal statements in favour of the Defendants raised “considerable doubts” for the court, but this matter was left open. Thirdly, and decisively, the LD held that the expert opinions “do not show, beyond the mere legal assertion, why the Defendants should be considered third party beneficiaries in the specific case”; in this respect, the expert opinions are essentially limited to general statements, but do not show the concrete application of the relevant US regulations (typically mentioned in footnotes) to the facts to be assessed here. It seems that the LD would have required a very specific and well-substantiated party expert opinion to be persuaded that the District Court of Delaware came to the wrong decision.

The LD also examined, and rejected, the allegation that a licence claim which includes the UPCA member states would arise as a consequence of any breaches of US competition or US antitrust law. The defendants were unable to present a decision of a US court that would confirm such a claim and that would be enforceable in the UPC territory.

Next, the LD examined and rejected the objection that the Defendants have a licence claim against Harvard under European law. In the court’s view, the Defendants cannot rely on an obligation of Harvard under European law to grant a licence to the patent at issue. The court further concluded that, even according to the submissions of the Defendants, a dominant position of the Claimants pursuant to Article 102 TFEU cannot be assumed; and even if a dominant position of the Claimants were to be assumed, its abuse is not apparent. The following discussion in the court’s decision show to what degree of detail the parties also quarrelled about this point, which in our view was rather ephemeral to the actual dispute:

The Claimants argued that the patented invention allowed for the first time the detection of 1,000 and more analytes in a sample in situ, whereas on the basis of the prior art it had at most been possible to detect a maximum of 6 to 10 analytes in situ in a sample. This was therefore a technology leap that made previously unattainable quantitative and qualitative findings possible, especially for research institutions. The Claimants' submission thus at least suggests the assumption of market dominance due to the superiority of the patent-protected technology.

However, the Defendants, for their part, have argued that the contested embodiment is technologically unique; research institutions and pharmaceutical companies rely on the contested embodiments for their work and cannot replace them with an alternative analytical method available on the market (opposition of 21 July 2023, paragraph 933). Compared to all other in situ profiling instruments available on the market, the contested embodiments could detect the largest number of RNA molecules in a sample. The methods used with the product were protected by patents from at least 9 patent families.

It thus follows from the parties' submissions that both sides refer to unique, non-substitutable and patent-protected technologies for the relevant product market, which potentially establish a dominant position. The submission thus provides indications for the existence of mutual dependence due to the respective alleged technological strength of the market participants. Accordingly, it cannot be assumed without further ado that the Claimants have unilateral market power.

On top of that, the LD Munich was of the view that even if there had been a dominant position on part of the Claimants, there is no abuse of this position by the Claimants. The present case was not an SEP constellation; hence the patent proprietor is in principle not obliged to offer to allow the use of the invention itself. Therefore, a concrete licence offer by the licence seeker on non-obstructive or non-discriminatory terms would have been required. Only if the patent proprietor refuses such an offer, it would abuse its dominant position. However, in the present case the defendants did not make a concrete licence offer before the oral proceedings, but merely requested, several times, that Harvard should offer them a licence. In the court’s view, though, Harvard was not obliged to tolerate the use of the patent at issue by companies that were not prepared to offer to conclude a corresponding licence agreement themselves. The licence offer to Harvard as made by defendants’ counsel at the oral proceedings was considered to be made too late, as Claimant 2) was not able to respond to it at the oral proceedings. Moreover, the offer did not pertain to past uses of the patent at issue by means of settlement and payment commitments.

F. Balancing of Interests

As in most of the previous sections of the decision, the LD Munich first set forth the standard according to which the UPC should decide the questions at stake:

Pursuant to Article 62(2) UPCA (Rule 211(3) RoP), the court shall exercise its discretion to balance the interests of the parties with a view to granting the order or dismissing the request; in doing so, all relevant circumstances shall be taken into account, in particular the possible harm which the parties may suffer as a result of the granting of the order or dismissal of the request for an order. In exercising its discretion, the degree of probability to which the court is convinced of the existence of the individual circumstances to be included in the weighing up is also crucial. The more certain the court is that the right holder is asserting the infringement of a valid patent, that there is a need to issue an injunction due to factual and temporal circumstances and that this is not opposed by possible damages of the opponent or other justified objections, the more justified the issuance of a prohibitory injunction is. Conversely, if uncertainties exist with regard to certain circumstances relevant for the weighing up of interests which undermine the court's conviction, the court may consider as a more lenient measure the alleged infringement to continue subject to the provision of security or even the dismissal of the request.

Applying this standard to the facts of the case, the LD Munich concluded that the Claimants were entitled to file the application and that the patent was infringed with a very high degree of probability. The LD was also convinced with a significantly higher probability that the patent at issue is valid; this conviction is not diminished by the auxiliary request submitted by the Claimants at the suggestion of the Local Division during the oral proceedings, in which the patent at issue is asserted in a restricted form. The LD was

also firmly convinced that provisional measures are necessary due to the infringement of a valid patent, both in terms of subject matter and timing. Additionally, the Local Division also did not consider the possibility of long-term harm caused by the order for provisional measures or their dismissal to be unilaterally to the detriment of the Defendants.

The LD further rejected the Defendants’ objection that a prohibitory injunction would be disproportionate because the contested method is “a completely subordinate part of a larger, complex product” for both factual and legal reasons. The court also did not follow Defendant’s argument that claimant Harvard would just be a Non-Practicing Entity (NPE) and thus have no interest in a prohibitory injunction. The court countered that according to Art. 62(2) UPCA, in particular possible financial damages can justify an injunction.

Defendants further argued that a prohibitory injunction would be disproportionate because the contested embodiments were non-substitutable and thus of irreplaceable importance for research into a large number of serious, life-threatening diseases and the development of therapies against these in the UPC Contracting States. The LD Munich, however, did not buy this argument at all. They pointed out that defendants themselves had claimed that claimant 1’s products were “competing” with theirs and that Claimant 1's products substitute those of the Defendants in such a way that the market would be blocked for the Defendants' products even in the event of a prohibitory injunction being lifted. Under these circumstances, concluded the court, it cannot be assumed that the contested embodiments are products that cannot be substituted on the market. The court also found that there no concrete and verifiable evidence was presented for defendants’ allegation that the research activities of third parties would be unduly inhibited if an injunction was granted.

Defendants further alleged that claimants were about to generate an unlawful thicket of invalid patents to prevent others from entering the market with analytical devices that allowed for the simultaneous detection of a multitude of analytes in a biological sample in situ. The court was again unconvinced, noting that at least the patent in suit is valid in the court’s view and that the parent patent also appeared valid, judging from the preliminary opinion of the German Federal Patent Court. Before this background, the LD Munich saw no concrete indications for a thicket of invalid patents.

Finally, the Court rejected the Defendants’ argument that a case as complex as this one is a priori unsuitable for provisional measures:

In view of the provisions in the UPCA and the RoP, the Local Division sees no evidence that the UPC should refrain from ordering provisional measures in the case of highly complex technologies and due to the large number of issues to be dealt with (in this instance, admissibility, jurisdiction, capacity to act, existence of rights, US law, antitrust law, direct/indirect patent infringement). In its recitals, the UPCA precisely expresses that the UPC should be able to ensure rapid and highly qualified decisions.

It seems that this argument may not have particularly appealed to the court’s self-image as a highly competent court with both technical and legal expertise that should be able to handle even complex cases with ease.

In view of the above, the LD Munich came to the conclusion that the requested measures - essentially following the claimants’ request - were to be ordered without the provision of security and that a continuation of the infringement against the provision of security would not be appropriate.

G. Order

The Local Division Munich therefore ordered the defendants (in short):

- To cease and desist from using or offering from use a method according to claim 1 of EP 482 in the territory of the UPC member states

(direct infringement of claim 1 of EP 482) - To cease and desist from offering and/or supplying for use, in the UPCA territory, devices suitable for performing a method according to claim 1 of EP 482 for detecting a plurality of RNAs in a cell or tissue sample, without

(1) stating explicitly, conspicuously and prominently on each offer, on the first page of the operating instructions, in the delivery documents and on the packaging that the devices may not be used for the detection of RNA in a patented method without the consent of Claimant 2) and that a use for the detection of RNA without the consent of Claimant 2) has to be desisted

(2) imposing on the purchasers a written obligation not to use the devices for the detection of RNA without the prior consent of Claimant 2), subject to the imposition of a reasonable contractual penalty to be paid to Claimant 2), to be determined by Claimant 2) and, if necessary, to be reviewed by the competent court, for each case of infringement;

(indirect infringement of claim 1 of EP 482) - To cease and desist from offering and/or supplying in the UPCA territory for use of the method in the UPCA territory detection reagents suitable for performing a method according to claim 1 of EP 482

(indirect infringement of claim 1 of EP 482) - To cease and desist from offering and/or supplying in the UPCA territory for the use of the method according to claim 1 of EP 482 in the UPCA territory decoder probes suitable for performing a method for detecting a plurality of RNAs in a cell or tissue sample according to claim 1 of EP 482, without

(1) stating explicitly, conspicuously and prominently on each offer, on the first page of the operating instructions, in the delivery documents and on the packaging that the devices may not be used for the detection of RNA in a patented method without the consent of Claimant 2) and that a use for the detection of RNA without the consent of Claimant 2) has to be desisted

(2) imposing on the purchasers a written obligation not to use the devices for the detection of RNA without the prior consent of Claimant 2), subject to the imposition of a reasonable contractual penalty to be paid to Claimant 2), to be determined by Claimant 2) and, if necessary, to be reviewed by the competent court, for each case of infringement;

(indirect infringement of claim 1 of EP 482) - To pay to the court a (possibly repeated) penalty payment of up to EUR 250,000 for each individual infringement of the preceding orders

- To pay the costs of the proceedings.

In all other respects, the request for provisional measures was dismissed, and the requests made by the Defendants were dismissed. The Court’s orders were declared to be immediately effective and enforceable, and the amount in dispute was set at EUR 7 million.

H. Comment

The injunction against NanoString will be in effect at least until the UPC issues a final decision on the main infringement actions based on the same patents, likely at the end of next year, or until EP’782 is revoked in parallel EPO opposition proceedings. NanoString can appeal the grant of the PI and has reportedly done so. Thus, the present decision is not yet final.

In any case, it is apparent from the decision that the UPC judges were fully aware that a new court has to prove its quality to give more parties the confidence to litigate their patent disputes there. They are succeeding. After the first UPC decisions have been published more actions have been filed. Soon the UPC will have to adjust its resources to continue to deliver on its promise of fast and well-founded decisions.

back